There are lives that touch us keenly. Some who walk among us leave a special imprint on our souls. One such person whom I am moved to call my very good friend died this week. I wish to share with you this remembrance:

“Quelle vie merveilleuse j’ai eue ! Je regrette seulement de ne pas l’avoir réalisé plus tôt.” –Colette

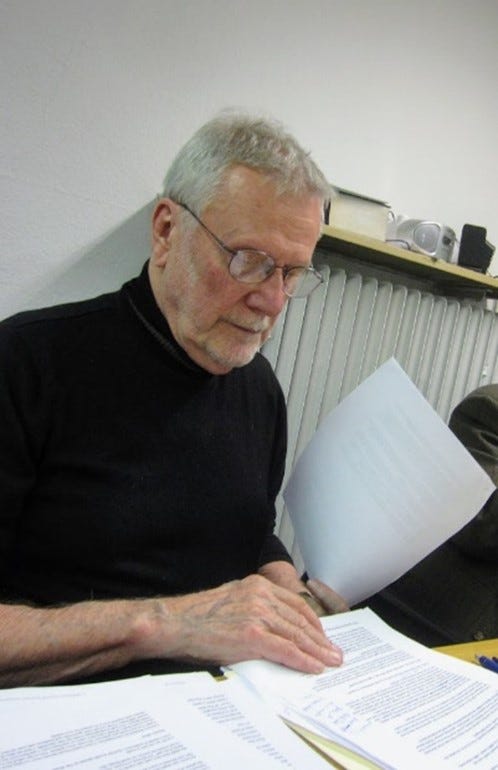

You see the sunset and yet you are startled when it grows dark. Our esteemed friend, our colleague, our compatriot William Osborne Kerr, Jr., Ph.D., died peacefully at 11:55 A.M. on Tuesday, January 31st, 2023, in the Helios Dr. Horst Schmidt Kliniken in Wiesbaden upon failing health. Family was nearby. Bill was born on May 5th, 1937, in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and grew up there and in nearby Stratford. His three daughters, Lauren, Rachel, and Jennifer, their families and loved ones, and untold friends and colleagues mourn his passing.

There is much to say. Writing about Bill’s life is daunting. If I may, let me start by recalling a parable many will know. It’s the one by American poet John Godfrey Saxe popularizing an apocryphal tale out of India. In The Blind Men and the Elephant, six blind men are led to such a beast. Each man touches a different part and tries to discern what the creature is like. The point is that each of us has his own truth to claim based on subjective and partial experiences. I will tell you about the Bill Kerr I know. You will of course have your own version of Bill to remember. He was multifaceted and he left many impressions.

People who think of Bill with special fondness are scattered across half a globe. He spent select years in the San Francisco Bay Area raising his daughters with his then-wife Joan. He took his undergraduate degree in philosophy at St. Bonaventure University in rural New York, the nation’s first Franciscan university, in 1959. His M.A. and Ph.D. in philosophy followed at State University of New York, Buffalo, in, respectively, 1961 and 1969. The life in California was thus bookended. His doctoral dissertation examined John Herman Randall, Jr.’s philosophy of religion. Randall, who died in 1980, was an American philosopher, New Thought author, and educator.

Bill taught philosophy at Santa Clara University, in the South San Francisco Bay Area, from 1967 through 1971, and he lectured otherwise elsewhere in his U.S. years, including at Rosary Hill College (now Daemon University) in Amherst, New York, during a time that included his master’s-degree year of 1961. He read and immersed himself in important discourse in his field. In 1968, after he was at Santa Clara, he published an article in Religious Education on perceived problems in understanding the nature of being human in relation to the university and institutional “confusion.” The foil for this article was a subject of Bill’s interest or admiration, Scottish philosopher John MacMurray (d. 1976), whose writings focused primarily on the existential nature of human beings. Already from these early years, we can see the roter Faden, the “red thread,” tying together Bill’s intense interest in the vital role of education as a political structure in the formation of its pliable charges.

I’m skipping around in dates and events here because that’s how I’m remembering it from snippets of what I learned in long conversations over years with Bill, and because that’s how Bill’s own mind also seemed to me to work: helter-skelter, I might say. (But in a good way.) Returning to 1961, Bill published a short thing, a book review, in Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, the seminal journal edited for forty years by Marvin Farber, himself a prodigious mind and later, if I am recalling this right, the chair of Bill’s Ph.D. dissertation committee at Buffalo. Bill told me a few anecdotes about Farber in passing that I am unable to repeat here for various reasons that include my bad memory. Suffice it to say, though, that such stories from Bill were always amusing.

While I’m still reciting a history of the Bill of long ago, I should not fail to remark that he served as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army in 1965-67 at Fort Bliss, El Paso, Texas, to fulfill an ROTC commitment. Later he would teach on board ship for Chapman College. The adventure coalesced when he “graduated” to “landlubber-professor,” as I might put it: for the ensuing 45 years, he would teach active-duty servicemembers stationed in Europe for the University of Maryland University College, now known as University of Maryland Global Campus. UMGC had and has its own cadre of traveling professors. In any case, many of you who will be missing his camaraderie now were his colleagues at Maryland.

Bill’s wide-sweeping interests were hard to pin down, whether by subject matter or geographically. Many of us now wishing to celebrate Bill’s life and singular existence are or were, as he was, expats. We are, or for swaths of time have been, ragtag uproots from our native land. Some of us perhaps engage in undue effort justifying to ourselves – if not others – our choices in that regard. Bill did that too. In any case, many or most of us are intellectually or academically accomplished individuals. But this “expat” gig embraces a particularly philosophical side to life. We are all thus philosophers, at least in some ways. We can connect on that level to Bill’s “transitory” sojourn of four-and-a-half decades – a good half a lifetime – ensconced in Germany. Still, it wasn’t simply escapism. I remember a dialog in the usual café a handful of years ago with a military wife, the spouse of a lieutenant colonel we had met, who mistakenly thought expatriate meant a “lapsed patriot.” It was a disparaging belief. As you probably know, the word does not mean that. It simply means one who chooses to reside away from his homeland.

So, was coming to Germany just another Zwischenstopp on Bill’s global itinerary? My understanding is that it started that way. I think he pondered it retrospectively. Even at the end, he continued to eye “retirement” in a bucolic native lakeside scene with close compatriots. I had the sense, those final weeks, that he had reverted to this as a waking dream of sorts, but that he knew on a deeper level what all of us surely know: “Civilization has clocks; nature has time.” (That’s a quote I once shared with Bill by an anonymous hospice patient, as stated to German composer George Alexander Albrecht.)

Bill was always interested in the hortative, in dialogue, in the didactic, in instructing and nudging the rest of us into living a well-reasoned life. This also impelled his ceaseless interest in politics and in social and institutional, as well as private, justice. But he was candid enough about his own flaws as a mensch among the rest of the thoughtful participants in ongoing social and cultural adventure. While every one of us falls short in many ways, most are afraid to look hard at the dynamic. Bill wasn’t. He examined it, poked at it; talked about it. He looked at what psychology might reveal about turbulent inner landscapes. He would earn a second M.A. in psychology, even. He read broadly in more fields than I could name in this reflection about him. He attended seminars. He meditated. He tried out as many alternative approaches as seemed plausibly to hold some promise or secret. He volunteered, or perhaps agitated is a better word, in faculty politics and causes.

His interest in culture, literature, film, art, dance, music, theater, and more was close to unbounded. He gave dance classes in the day, including some with colleagues who might read my words. I have a writing excerpt of his detailing what life was like for him as a youth in post-WW-II New York in the forties. It follows his usual free-association, irreverent style that captivated his listeners so easily. He wrote fascinating narrative chapters and stories over many years in an ongoing series that would become known as the “Edward” sequence. Here’s a bit from one:

When Edward was seven, he and Anita Heffron, a short, strong brunette of eight, were playing with matches in the wooded lot on Ravencrest Drive, in late August. Anita wore blue shorts and had nice legs. Edward sweated in dungarees.

A lit match somehow fell on the dry, knee-length grass and a blaze started, worthy of a neighbor’s call to the fire department. Edward and Anita escaped quickly to the woods across the street, where they had built a “hut.”

The fire truck arrived and the fire was gone in minutes.

Anita and Edward watched from the woods across the street where they had fled, and a firefighter who saw them, authentic in his red hat and black rubber raincoat, came over. Various neighbors were on the street, watching.

“Do you kids know anything about this?” he asked.

That’s taken from an edit Bill sent me in 2013. It has a quiet sweetness to it. But I’ll reveal that the Edward sequence tested limits in other ways not seen there. Edward stands for Bill’s Mr. Hyde aspect. Edward is Bill with the restraint of social awareness and control removed. Edward’s escapades, which traverse all ages from early childhood through advancing middle years, flaunt mores and values in sometimes disturbing, but always provocative, ways. The adventures reflect a distortion of Bill’s inner mind. They reminded me more than once of, for example, Philip Roth.

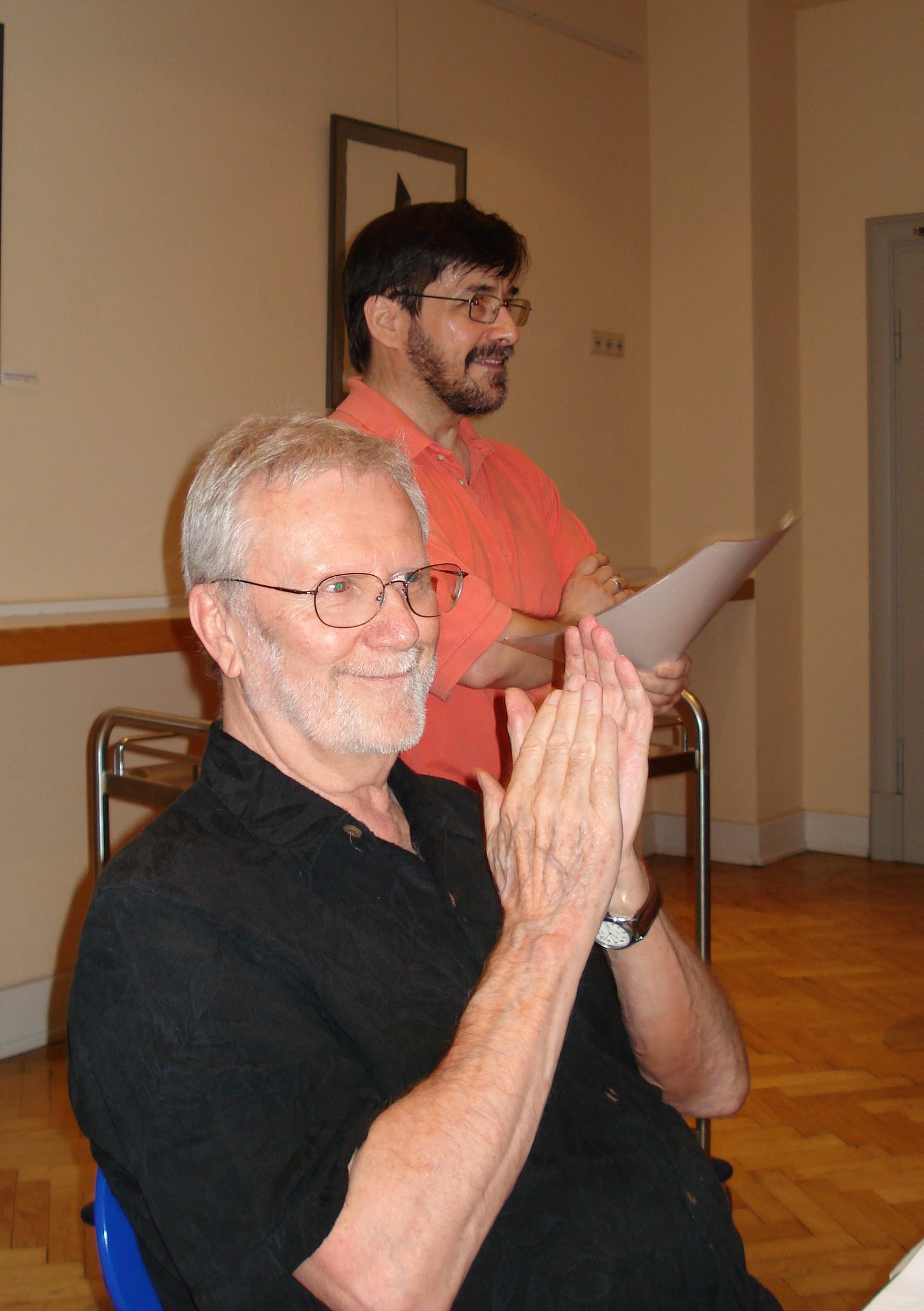

“Edward” was part of Bill’s attempt to find and palpably probe his own foibles and strengths as a human being. The room where the Heidelberg Writers’ Group met stayed noticeably hushed for a moment after Bill would read Edward to us aloud. We want to like Edward. And yet there is conflict.

“The fact that we all die and life is roughly about two minutes long is a big problem, because we spend so much energy trying to deny it.” –BK

Am I allowed to say that Bill struggled with attempts to confront his own death with the equanimity he felt a philosopher should have? He used to carry a book around for months, maybe years, on the subject and talk about it frequently. Ponder it. The book was The Denial of Death, by Ernest Becker. In email one year ago, Bill wrote:

I do think that fear of death explains the core of religious myths, and just about any other hope-filled narrations running around in human culture… My going hypothesis in this is in Becker's Denial of Death… Becker constructed a long defense of his belief in God on the basis of the notion of transcendence. How he gets there is beyond me, but I frankly have postponed a closer look, because I suspect he just gave in somehow…

As to Becker, one earnest reviewer has called it one of the most profound and provocative books of the 20th century. In any case, it captivated Bill for a long time. A philosopher’s special hell, that subject might be, I suppose. I recall Bill’s confiding about his mother’s attempts to mollify him about death when he broached it with a fright we might imagine from a boy who has begun to perceive with an abstract mind and to apprehend anxiety. That his own mother died not so long thereafter was a private curse he endured.

Here’s Edward again.

I. Scenes of Early Life, in which Edward meets with a violent nature, animal fear, matron styles, industry, consanguineal friendship, the possibility of spirit worlds, and other human elements.

…

When Edward was four his friend Paul was with his mother at the bus stop. Edward found them and hit Paul on the head with a claw hammer.

He was once trapped behind a fence by a barking Fox Terrier with revolting white fur and an absurd mustache.

He dreamed that a circus lion escaped and chewed off a generous portion of his aunt’s plump leg.

Bill experimented in so many ways. There were meditational summers at Big Sur in those hippie days. He taught some of this stuff, even. There was an endearing, rascally waggishness to him that we all knew and appreciated. There were extensive intellectual exchanges on most any subject; lengthy correspondences and phone calls; irreverent laugh riots; poetry slams; you name it. Luncheons with colleagues. Arguments about Kantian ethics, imperatives, or theology. There was a maddening procrastination, too – a weakness I happen to share, to my detriment.

Bill was a romantic, as we see from Edward:

The sun is too bright on her eyes, so she squints, but her light smooth skin has a movie star quality, like Jean Tierney’s, or her Betty Grable hair could be put in a net overnight and she still would be gorgeous, because of those … lips, painted with lipstick bright as blood, and her green, unsuspicious eyes.

But other times, he was a romantic about Wittgenstein. Or he tried and tried, like many have before and since, to get Heidegger. Now, there’s a puzzle! Here’s the final line from Wittgenstein’s great Tractatus, his aphoristic masterpiece exploring the relationship between language and reality as it aims to define the limits of science: “Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen.“ (“What you cannot speak of, you must be silent about” is an admittedly poor translation.) Bill taught me that line. He was careful to recite it in German.

Bill fell a lot. He once told me about a neurological condition by which one foot tended to drop or hang behind. That led him to experience several personally famous falls. He bragged about some of them. There was the time in front of the Hauptbahnhof – main train station – when he fell and broke his cheekbone. That was fifteen or twenty years ago. More recently, he fell while walking with Marylander friends and acquired a hairline fracture to his pelvis. He recovered. There were some weeks of forced encumberment in his flat and ordered-in food delivery. In September 2022, age 85, he loaded up his rucksack with groceries and traipsed the granite staircase to his door. As he told me some days later, he fell backward and landed on his pack, arms and legs flailing helplessly skyward like a flipped-over turtle. He showed me his purple bruises all along his upper arm and torso. He laughed recalling his helplessness and recounted how a young apartment-dweller neighbor – a foreigner from somewhere near the craggy historical cradle of humanity who spoke no English – rescued him.

We were in the Heimathafen Café, our frequent retreat a couple of hundred meters from his place, when Bill related that latest excitement to me. It was the last time I saw him aside from hospital or care-facility visits: he was taken by ambulance for acute-care skull surgery two weeks later, the second week of October, after he fell unconscious at home from a subdural hematoma. It was surely a belated complication from his stairwell tumble.

Roughly seven years ago, he suffered a “minor” heart attack and wound up sporting a triple bypass. He recovered rather magnificently thereafter in only a few months. It was wonderful to see him bounce back from the precipice that time. Bill’s humor never abated – not then, and not when he recounted with high drama a favorite mishap about driving his car off the curvy road toward Schlangenbad late at night in deep fog. He bobbed off the guardrail and damaged a tree. That time he was unhurt. He drove home. I’m telling you this because he savored retelling the story; I heard him tell it four or five times over the years. He enjoyed describing his conversations with the police unit in, respectively, broken German and halting English the next day. He waited for a bill from the city, but one never came.

There are stories and stories. You undoubtedly know your own set of magnificent ones. One day we can all reminisce once more and tell them to one another.

The Elephant parable I alluded to earlier was also a moral tale about the meaning of religion. That was Bill’s philosophical bailiwick: he pondered humanity’s need for religion and its purpose from different angles or aspects over most of his life. His conclusions changed over time. Last summer, he wrote in email:

If you grant that religion is a projection of human longing, with mortality a nasty stumbling block, and with Freud on the right track, then an updated Christian theology would be that of [German-American Christian existentialist philosopher, religious socialist, and Lutheran Protestant theologian Paul] Tillich…

I am at the point where, while I can see that religion is a kind of art, a comfortable place where death is resolved into a possible victory, it never quite seems preferable over science, … [with its demonstrated] advantage over chanting by the hospital bed…

Science tests out and you can change things for the better. Planes fly. Reliably. Angels don't, really, but they give us a strong suggestion for the better. Angelic virtue. Nurses have it. Nuns pretend. Are Mary and Joseph our best model couple? Not according to Nietzsche.

From another mail message a few months earlier:

In my currently developing theory of everything, I do think it's death that we constantly overlook as a reason for so much in religion. The fact that we all die and life is roughly about two minutes long is a big problem, because we spend so much energy trying to deny it.

So, there we see some of the wide-ranging conversation – with, in part, himself – that fascinated Bill until the end. The multifarious chain of postulates and cerebral reflection never ceased. Nor were they ever stultified by misplaced reverence. The jocular asides never stopped. They were part of what made the quest for reason work its highly personal magic for Bill.

In the end, what is real and what is imagination? These rambling reflections upon Bill’s demise explore what was for me real enough about Bill. You might nod your head at some of it and wag a finger at other parts. You will necessarily have a different Bill in your thoughts. Each version is worth cherishing and sharing. Bill spent a lifetime examining where the line between subjective reality and externally verifiable truth might lie – if, indeed, it is something we can identify and authenticate.

A number of you, Bill’s yeoman friends, rallied to his aid in his final weeks. Some came in from afar! It was a powerful attestation to his personal sway. The plan now is for Bill to be cremated and for the ashes to be interred in Connecticut in the family plot.

Again, as Colette so aptly put it (this time in English), “What a wonderful life I’ve had! I only wish I’d realized it sooner.”

In memoriam,

Dallman Ross